The Infographic Industrial Complex: Will Instagram Posts Save the World?

May 5, 2022

The industrial complex is a socioeconomic phenomenon where businesses interweave themselves within social and political systems. This commensal relationship negatively impacts the consumers of these profit economies. While the initial intent of these businesses may be to advance its host institution toward its end goal, it bolsters profit during the process. The industrial complex is notorious for its perpetuation of social issues in exchange for financial gain.

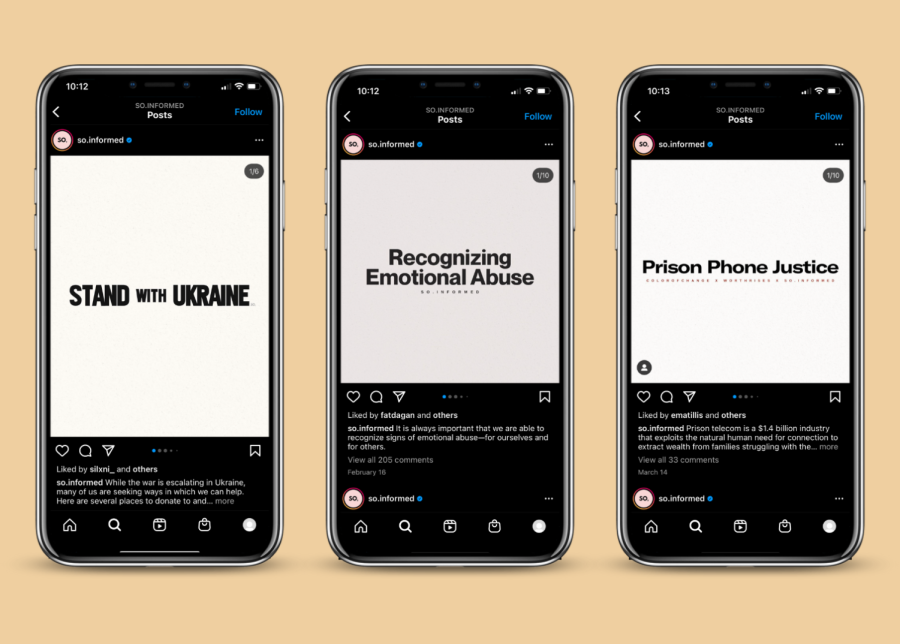

Individual designers, brands, and governmental organizations are the perpetrators of the infographic industrial complex, leeching on activist movements to generate profit and/or popularity. However, unique to this complex is the use of social media as a medium. Anyone can make an infographic and everyone has a platform to share them on. The infographic industrial complex has evolved into a form of performative activism utilized by the masses.

Performative activism is defined as using social gain as a primary motivator for activism. This term is often coupled with slacktivism — or activism requiring minimal effort that yields insignificant results.

Following the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, Instagram infographics transformed into vehicles to signal wokeness and generate profit, jamming Instagram feeds. Posts about Black Lives Matter attempted to disseminate bite-sized information on a massive social issue.

However, infographics have existed long before then. According to Dr. Murray Dick, the author of The Infographic: A History of Data Graphics in News and Communications, the emergence of infographics at the end of the 18th Century was practically inevitable. During the late Enlightenment period, the number of works and studies being published spiked exponentially. More and more people were collecting and generating data to use in textbooks, reference books, and other academic publications.

Eventually, researchers began to look for a clear, visual alternative to presenting their dense data. Scottish engineer and economist William Playfair had conceptualized bar charts, pie charts, and line charts to drive the creation of infographics.

In the beginning, infographics were catered to a niche audience. “[The infographics] were very much bound up in an elite discourse,” Dick points out, “…elite people talking to other elite people about elite issues.”

As it evolved, the exclusivity of the infographic audience began to metastasize to the general population. At the turn of the 20th Century, newspapers and magazines began to regularly publish infographics, realizing it appealed to their audience to have a concise visual representation of an article. Infographics eventually became weaponized as political tools for political persuasion.

Today, infographic posts are catered to the general public. They are designed to be easily understood and aesthetically pleasing to drive their proliferation. While its convenience may yield positive impacts, its vast oversimplification of intricate issues proves to have many ramifications.

The Good

Social media is the primary news source for Generation Z. Thus, infographics propagating Instagram foster a more politically aware generation. Danielle Estagle, a sophomore at CHS, says, “I do feel that these infographics are helpful because they keep me educated and aware of relevant topics in today’s world that I would otherwise not know much about.” Katie Lien, a sophomore, agrees, saying, “I think that Instagram infographic posts generate a positive response that has the potential of igniting passion and interest.”

Not only do these posts increase awareness of large-scale issues, but some people may be encouraged to take their newfound understanding to the next level.

Oftentimes, infographics on social media will have links to donate/ petition for specific organizations. “I have used the petition/resource links very often,” Lindsey Nguegang, a sophomore, asserts, “Some of them were for removing people from the death sentence and others were to hold officers accountable for the killings of innocent black people.” Infographics have the potential to aid in ensuing change, whether it be by directly garnering signatures for petitions, or stimulating action and passion in individuals. However, this goal is often muffled by the spread of misinformation and performative activism.

The Bad

Trivial infographics do not have the power to dismantle intricate social issues that have been ingrained in our society for decades. Because these posts aim to present complicated issues in a concise manner, infographics often fail to address the complex nuances of a situation, such as a war or microaggression.

Additionally, the popularity of infographics has burrowed a breeding ground for performative activism.

During the Black Lives Matter Movement, a slew of non-Black people spoke up about race when they had previously never mentioned it. This raises the question of whether or not their activism is genuine or if they are simply conforming to popular behavior.

An anonymous student states, “I have questioned whether people’s posts about movements like BLM were genuine or posted for the sole purpose of following the crowd, with movements being long overdue.” Amanda Maryana, a student at NYU, agrees, stating that she “was… shocked because I never personally witnessed so much support for BLM in one place at one time.”

Celebrities with a large following are especially prone to performative activism, as not posting something about a certain cause is synonymous with opposing a certain cause to too many people. Pressure to appease their audience drives influencers’ activism, making their seemingly genuine activism shallow and artificial.

In order to avoid performative activism, one’s virtue signaling must be conjugated with actual activism.

“I oftentimes tend to see them as trivial posts,” said Katie Lien, a Castaic sophomore, when asked about her personal response to frequently encountering infographics on her social media feed. These 1080 by 1080 aesthetically pleasing posts are repetitive, performative, and desensitize the gravity of the issue they are demystifying.

Another dimension of the artificiality of the infographic industrial complex is the selective consumption of media. Users will likely only repost content that aligns with their views rather than those that challenge their opinions. This generates an echo chamber of posts that only reverberate a particular point of view. This has the potential to distort a consumer’s holistic perception of a mass issue.

The Ugly

After George Floyd’s death, BLM posts plagued the feed of hundreds of companies, professing their commitment to racial and social justice.

Walmart pledged to stop locking “multicultural” hair and beauty products. Sephora committed to devoting 15% of its shelf space to black-owned beauty products. LEGO suspended marketing for police-themed sets.

Prior to George Floyd, these companies had never pledged as much support to the BLM movement. It’s likely that the support of these companies towards the Black community is performative allyship, and was only motivated by profit.

Further, the formatting and aesthetically-pleasing nature of these posts act as rose-colored glasses on a sensitive subject. In doing this, the impact of reading about a mass atrocity, such as the Russia-Ukraine War, is mitigated, thus desensitizing people to the gravity of the issue. On the flip side of the same coin, it is often the most attractive posts that get reposted, rather than merit driving the posts’ proliferation. This only compounds the artificiality of the posts.

“It makes me question whether the chance to spread awareness through social media is worth it at the expense of authenticity,” said an anonymous student. When it comes down to it, do the benefits of online activism outweigh the costs?